A Science Symposium Keynote Experiment

Thinking with, Returning, and the Middle: An Experiment in the Midst of Change

10th Annual Joel Barlow High School Science Symposium

June 5, 2020 via Zoom

When I was asked by Dr. Nuzzo about 3 weeks ago to deliver the keynote speech for the 10th Annual Joel Barlow High School Science Symposium, I was literally speechless for a few solid minutes. I proceeded to respond with an unwavering yes: “Challenge accepted; I will be there!” After my excitement peaked from the thought of returning (in some capacity) to Barlow and reconnecting (virtually) with former students, reality settled in. I sat myself down to let everything sink in. The next few moments were a bit of a blur, but I recall slumping down my chair, making myself temporarily small, holding my face up with both hands.

What now? Where do I begin?

Imposter syndrome quickly enveloped me—a phenomenon that is perhaps all too familiar among students and academics alike who hope to “make it.” I took a few days to sit with the swirling feelings and to reflect—2 practices that have become part of the fabric of my everyday life during this time of social distancing. I hope that after this keynote, you, too, might sit with the ideas and reflect on any meanings that the words may have evoked for you.

The keynote speech.

When I think about the keynote speech, I think of speakers who have “made it” in their respective careers. Just 5 years ago, one of my own mentors, Dr. Mala Radhakrishnan—a brilliant professor of chemistry at Wellesley College, a poet, a researcher, a musician, a mother—engaged us in a wonderful lecture about the micro world of drug design.

It feels a bit surreal that, 5 years later, here I am—a science teacher turned grad student and aspiring educational researcher—speaking with all of you as I’m navigating the at-times uncertain pathway towards “making it” in the world.

What does it mean to have “made it”?

Whatever “it” is—I know with certainty that I am still in the midst of it, making my way through the messiness that is “teaching, research, and life in the ‘real world’”—words that my mentor left for me, printed into a book of chemistry poetry. A collection of verses about life’s many phase changes and transformations.

Rather than focus on individual accomplishments, I’d like to invite you to actively participate in thinking, making, and feeling with me, as I retrace and weave together some of the enduring moments, inspiring voices, and generative tensions that continue to shape my life (and that maybe influence yours, too).

So, this keynote is about my life-in-the-making. It is about my life as I’ve made it my own and continue to make it, but always with others, in proximity to people I care for and about, working as a collective body.

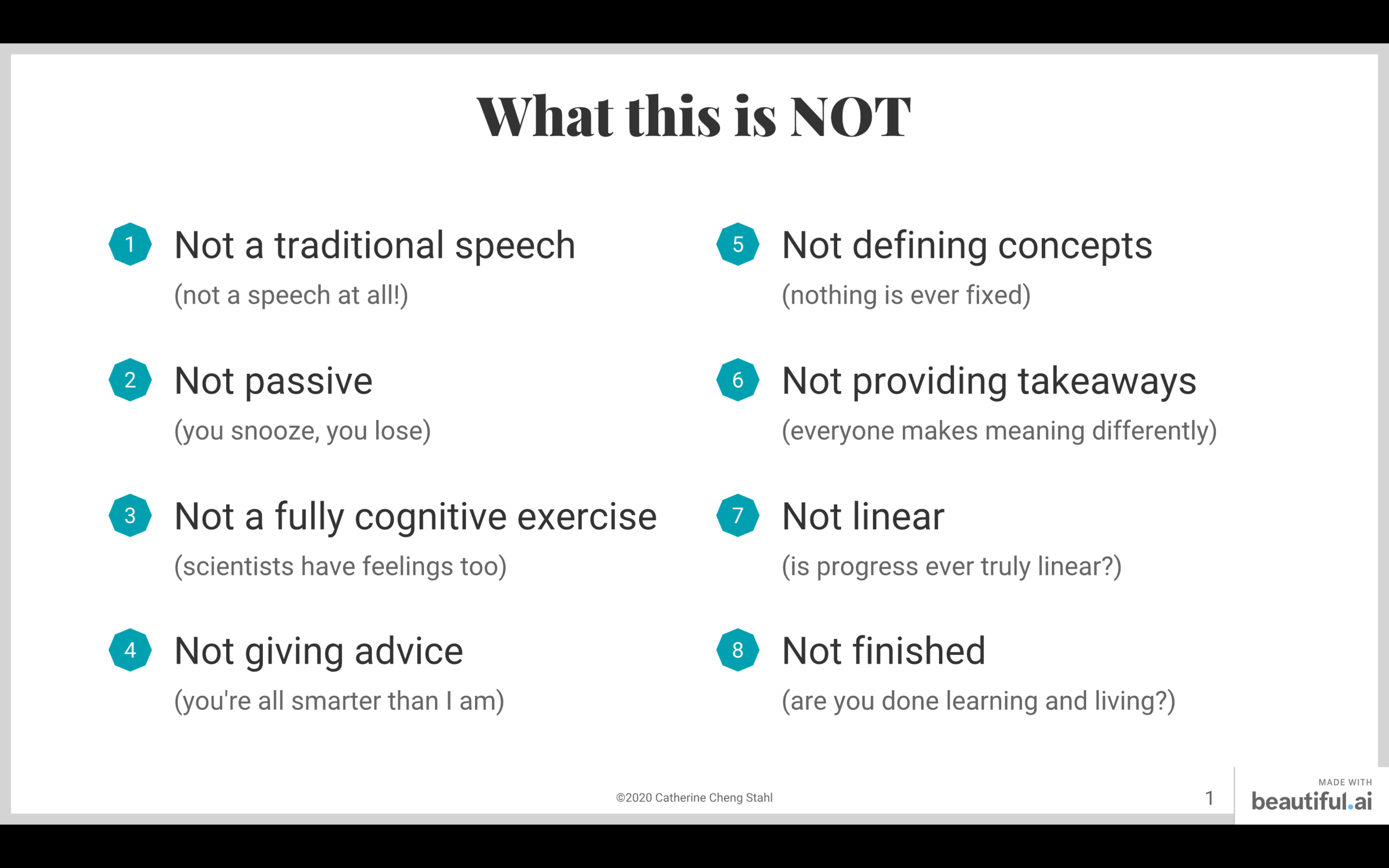

Rather than as a conventional speech, I approach this keynote as an essay in its most essential form—an attempt to play with ideas, or, an experiment of a different kind. This is part of an ongoing experiment in getting lost and turning back to find one’s way in the midst of climate change. This essay is intentionally fragmented to invite you to piece together the parts on your own terms, following your own timeline, to make meaning. There is no single right way of connecting the dots.

Video of Keynote Experiment

Research. Research—searching anew—searching for explanations, for understanding, for truth.

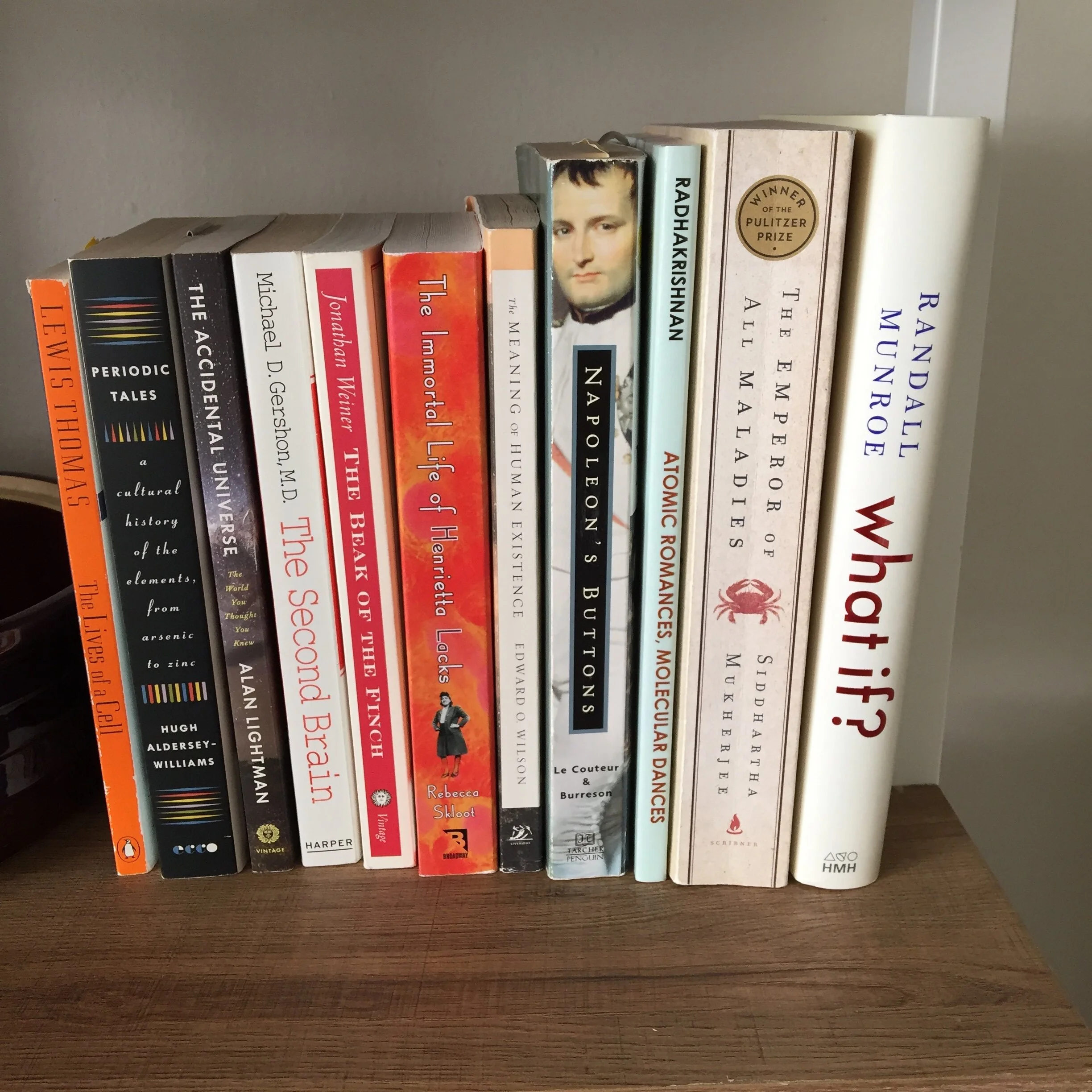

As part of my thinking for this keynote, I researched through my bookshelves, opening books gifted to me by friends, family, and students alike, turning over pages and re-turning ideas in my mind. By re-turning, I am thinking with the feminist theorist Karen Barad, who uses microlevel properties of physics (and sometimes biology) to theorize the social. She conceptualizes re-turning as a practice of turning something “over and over again,” not unlike earthworms turning the soil, “opening it up and breathing life into it,” and thus creating new configurations. This is a concept that I gravitate toward—as abstract as it may seem—and continue to hold on to.

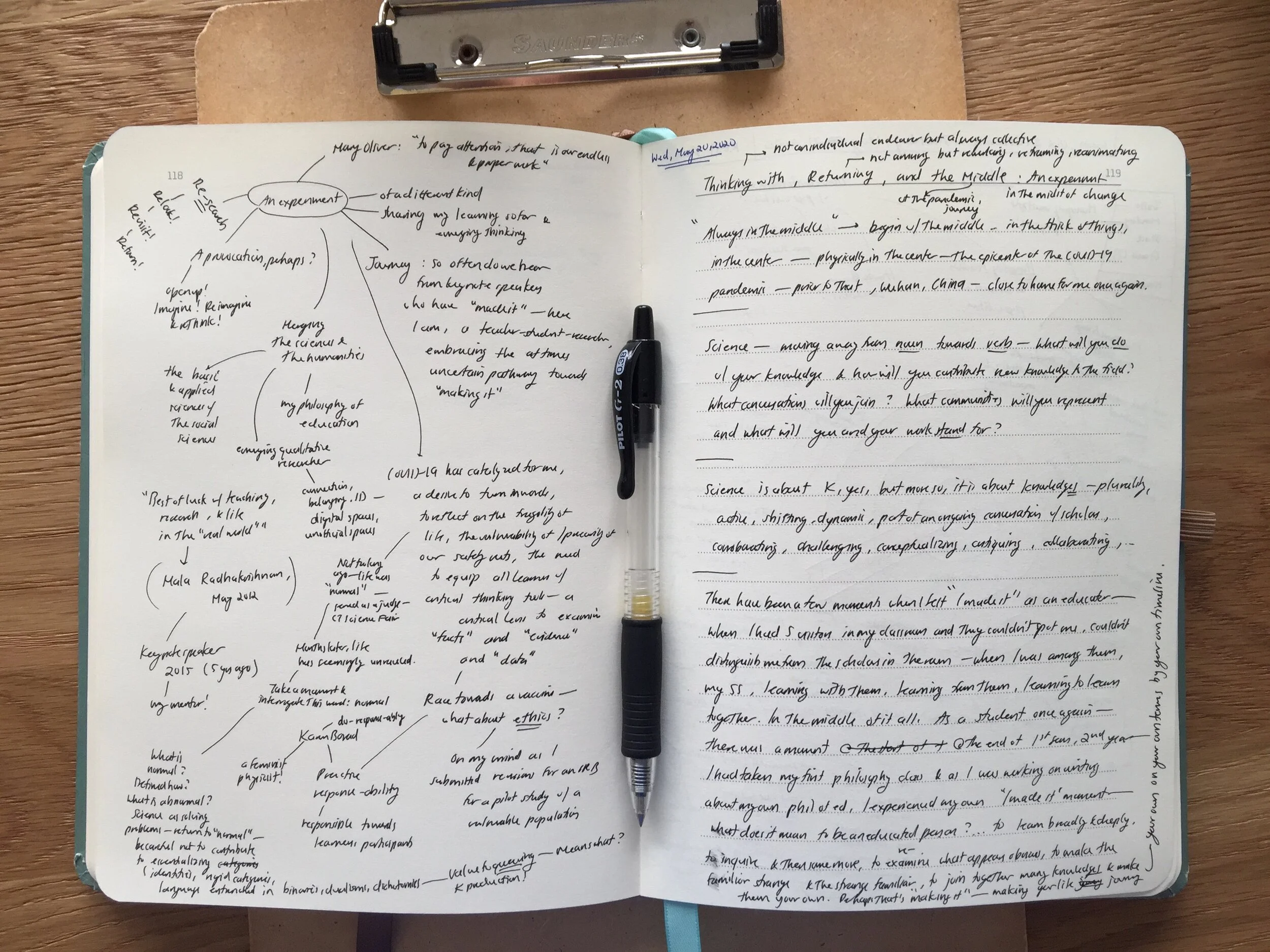

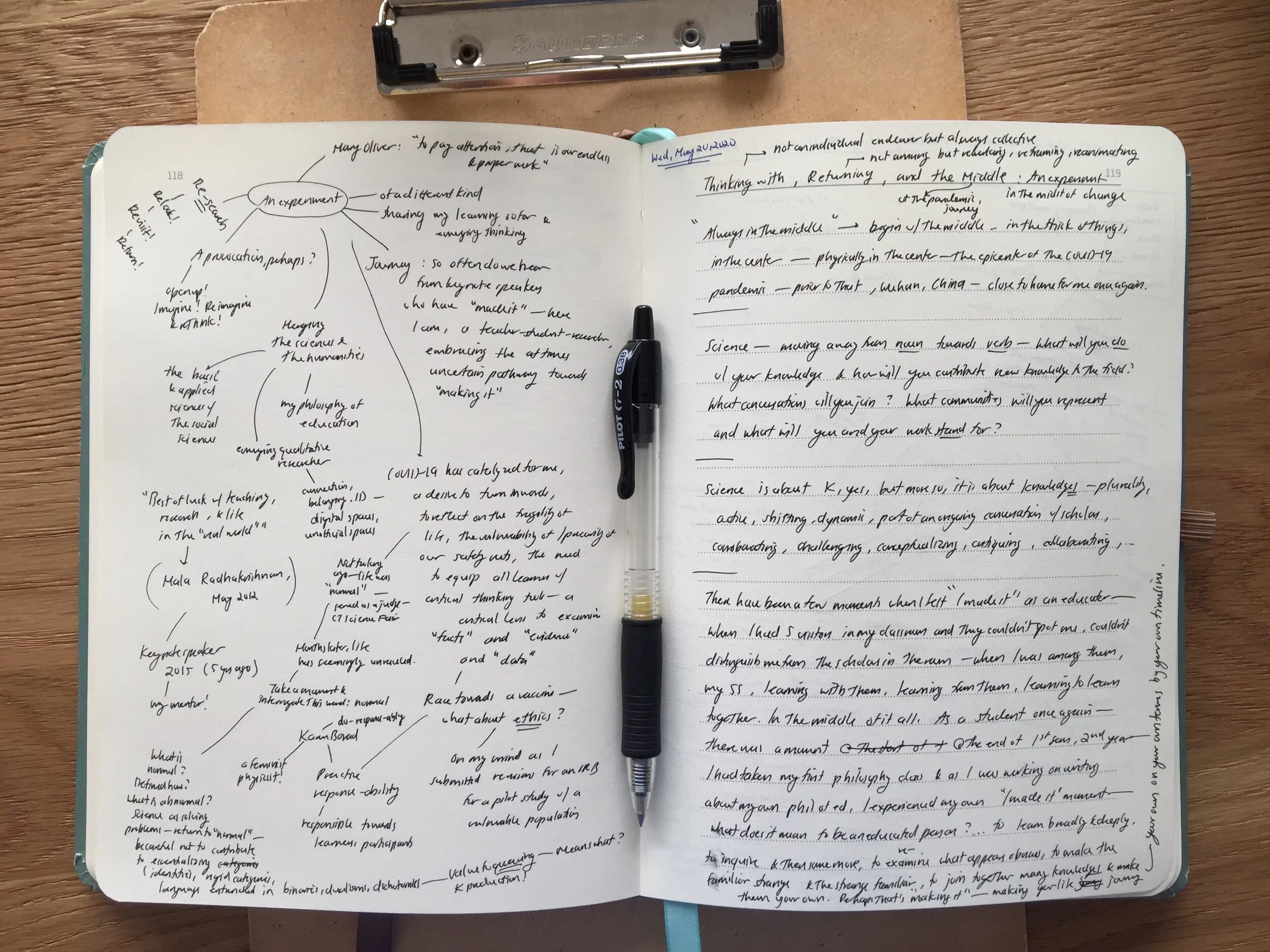

Beyond books, I also researched through my grad student notebooks—noticing, collecting, and assembling words, phrases, feelings that move me, move me forward and to step back, move me to make something new of words in a different context. Move me to make the familiar strange.

I, too, researched within, turning inward, asking myself:

What do I want the budding scholars of the present and the future to leave with?

What might I offer of my own life experiences—where I’ve been and where (I think) I’m going?

How might I rethink the keynote speech and respond to the many changes in our climate, the inevitable uncertainty, and the precarity, unrest, and fractures that constitute our reality today?

With so much swirling in my mind, I returned to my notebook with pen in hand and just scribbled whatever emerged. Among the first phrases that I wrote were “thinking with,” “returning,” and “the middle.” Thinking with. Returning. The middle.

Taking the directive of “always in the middle” from philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, I turn to the middle, in the messy center, in the thick of things, in one of the epicenters of the coronavirus pandemic: New York City. This is where I live a life in-between, moving through physical and virtual spaces; traversing disciplinary boundaries (from the “natural sciences” to the “social sciences”) and constantly shifting roles as student, teacher, researcher, writer, partner, friend, daughter, sister, and…and…and…

This life in the middle is new for me, and perhaps for you, too. For many of us, living the outside life indoors has been a challenge—one that we are still navigating, sometimes alone. This new climate is unsettling and disorienting, particularly here in the city, where for this entire past week, citywide curfews have been in effect to keep bodies inside, to “ensure order,” to “prevent violence.” It is within this shifting landscape that my experiment is situated—a landscape that has emerged from the background and precipitated into a kind of “terrain of struggle” (to borrow from Stuart Hall) for voice, justice, and change.

I am still in the midst of attempting to process all that is happening around me and those I love and care for. I have been sitting with feelings and emotions of my own, alongside those of my Black friends and colleagues, re-turning the events, actions, and reactions—on the streets, on mainstream media, and on social media—all while engaging in self-work, or the work of looking within myself, around me, and beyond me.

This time of COVID-19 has been full of disruptions, interruptions, and fragmentations on a whole different scale. For me, though, this time has also been a period of forging connections.

Deeper connections with colleagues made possible with Zoom technology, which helps in collapsing the physical distance separating us, bringing us into each other’s habitats.

I’m simultaneously cultivating caring connections with family, as we figure out different ways of living with one another, supporting each other, and creating personal space while sharing the same small space.

There have also been inward connections as I reflect on my seemingly disjointed movement through the world so far. I am what some call an ABC—an American-born Chinese—although, the truth is, I’m more of a CBA—a Chinese-born American. I self-identify as Asian American, straddling two at-times irreconcilable identities, living a kind of hybrid life. I studied biological chemistry and art history during my undergraduate years at a women’s college. I belong to a family of doctors; my parents hold medical degrees, my sister is applying for medical school, and my partner is a hematologist/oncologist in training. Although I was on the pre-med track from middle school through senior year of college, I eventually ventured off course against all expectations, following a kind of “gut feeling” that has guided much of what I do, and established my own path to become an educator, but not before exploring life as a biomedical researcher. Today, I am pursuing my doctorate to become an educational researcher. I tell my mom I am on the path to become a doctor, just not the kind she had hoped for.

My life over the past 30 years has consisted of twists and turns and re-turnings. I am still grappling with how to join together what seems so far apart. How do I reconcile my past training as a researcher of protein tyrosine phosphatases and the human Notch protein with my current pursuits as a researcher of youth identity constructions and belonging in digital spaces? How do I bridge my teachings of biology and chemistry with a course on gender, difference, and curriculum?

Both of these questions point to a larger philosophical question of how do we piece together the many contradictions, tensions, and fragments in our lives into a cohesive whole, or what W.E.B. Du Bois calls a “workable equilibrium”? Said differently, what do we do with all that we know and learn? What do we make of our studies, our research, our stories?

“To pay attention, that is our endless and proper work”

-Mary Oliver

“To pay attention, that is our endless and proper work.” These are the words of the late poet Mary Oliver, whose work I encountered in my AP Language class back in high school. Her words spoke to me during my messy adolescent years, and today, they carry resonances that are hard to ignore. To pay attention is not the same as to observe. My own training has taught me that observations have an objectifying effect. The observer is always in a position of power, with authority, controlling the gaze and framing the narrative. I acknowledge that observations play an important role in research, but used alone, they fall short in fully representing the observed because observations are bounded, capturing a moment in time, fixed in place.

To pay attention, I believe, is to go beyond the obvious, the then-and-there, to consider context, history, and the larger landscape. To borrow a concept from Du Bois, it is “a life-work” of self-work—of "looking within yourself, around you, and beyond you (this idea of self-work comes from educator Marylin Zuniga). It means living close within our ecosystem, attuning to what is happening in our local and global communities. It means paying attention to who is missing in the work that we do. It means noticing who and what is left out in our projects.

Part of doing self-work is also figuring out who we are and what gifts and resources we hold to support the ecosystem we are in. More than ever, this time of turning inward in the midst of climate changes (emphasis on the plural) has made me realize the important work of naming the injustices, indignities, and inequities that we witness and the necessity of orienting ourselves towards others around us who are the most vulnerable. It is our collective responsibility to protect the most marginalized among us.

I return to the middle. To the thick of it. To the messiness. The discomforts. The difficult conversations. What are the conversations we should be having in our research, particularly in the sciences? I’ve been thinking about this ever since my first semester back as a student. I feel it begins with all of us acknowledging the ways in which science has contributed to exclusionary practices while bringing about advancements and innovations. I feel it is recognizing how science has a history of dehumanizing and othering, of creating value systems and differentiating worth through categorizing, classifying, and sorting.

In my mind, I often return to my early days of teaching biology and chemistry, when some of my students, defeated after a first assessment, would meet with me, their eyes avoiding mine, confessing that they’re “not good at science” and “can’t do science.” I remember sitting with the students after school, reviewing the content they hadn’t yet grasped. It escaped me then to interrogate the question of what it even means to do science. Science is about knowledge, yes, but more so, I’ve come to recognize that it is about knowledges in the plural. Science is active, shifting, dynamic. Far from a solo activity, science is joining ongoing conversations with scholars, corroborating perspectives, challenging viewpoints, conceptualizing new ideas, collaborating across specialties, critiquing others in the same field, and destabilizing seemingly fixed concepts that we thought we had figured out. Science is iterative. It is cyclical. It is not a method; it is a return. It is re-turning: breathing new life into the old, creating novel configurations.

Just a few months ago, life was so-called “normal.” In February, a few days before I turned 30, I returned (physically) to Barlow to volunteer as a judge for the annual CT Science Fair. Months later, life has seemingly unraveled. This time of COVID-19 has catalyzed for me a desire to not only turn inwards to reflect on the precarity of life, the vulnerability of our safety nets, and the need to equip all learners with critical thinking skills, but also question this seemingly benign word: normal. What is “normal” and how is it defined? What does it mean to return to “normal” life, and is that even possible or desirable? What would we be returning to?

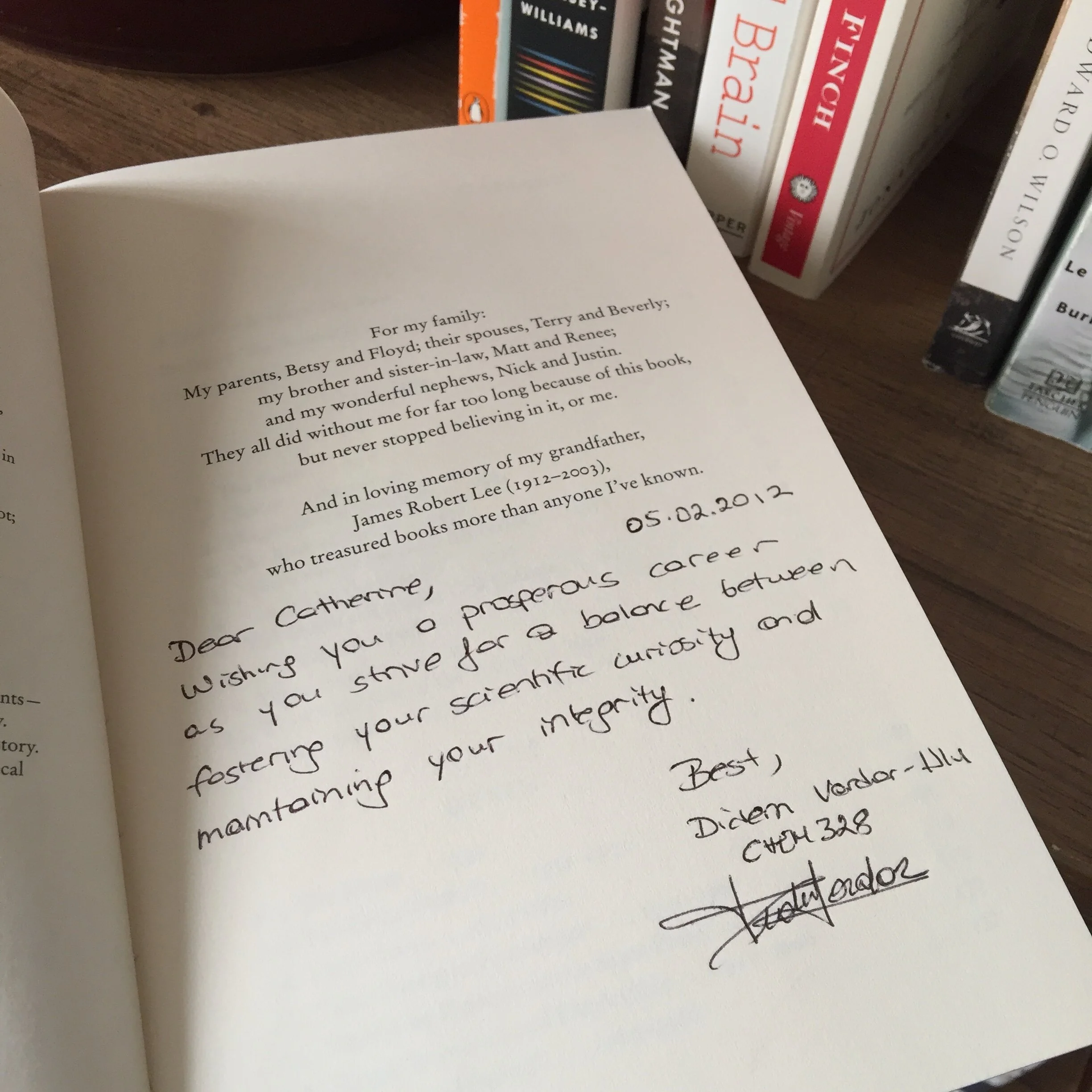

I’ve reached the age in which I give myself permission to buy doubles of clothing items. I’ve been living in the same leggings, of which I have two identical pairs. On my shelf, I also have two copies of the book “The immortal life of Henrietta Lacks”—both gifted to me, 5 years apart. The first copy was given to me by another mentor of mine, Dr. Didem Vardar-Ulu, a professor of biochemistry with whom I researched and taught. In this book, she wrote: “Catherine, wishing you a prosperous career as you strive for a balance between fostering your scientific curiosity and maintaining your integrity.” These words, from 2012, remain engrained in my memory. How do we engage in research responsibly? To whom are we responsible?

A life in proximity has transformative potential

-Ocean Vuong

Returning to this notion of “making it” in our respective spaces. There have been a few moments in my own journey when I had the feeling that “I made it.” As a teacher here at Barlow, I remember one day when several former students visited our classroom and they could not find me. They couldn’t distinguish me from the students in the room, because I was moving among them, learning with them, learning from them, learning to learn together. I was in the middle of it all, learning to live with wonder and awe. Learning to live and lead with a beginner’s mind.

A second moment was when I circled back to becoming a student again. There was a moment at the end of first semester, second year of my doctoral studies. I had taken my first philosophy in education course and as I was drafting my own thinking towards a philosophy of education, elements slowly came together. What does it mean to be an educated person? For me, at the heart of education is enduring inquiry—a generous curiosity and eager openness to seek out what we do not know and to work through what we do not understand. This, I feel, is not separate from the goals of research and science, if we take both as a verb rather than a noun—that is, if we think about both as practices that we engage in alongside others, thinking with, and always in proximity to our communities.

To paraphrase from the poet, essayist, and novelist Ocean Vuong, whose book talks give me so much light and inspiration, “a life in proximity has transformative potential.”

I leave us with some questions to continue pondering…

How will we use our individual and collective knowledges, skills, and networks to benefit our ecosystem?

How will we continue to embrace science as a verb—as an inquiring mindset, a practice, a re-search—as we transition through phases of our lives?

How can we actively live with a beginner’s mind—with awe, curiosity, and wonder—even as we develop expertise in our respective fields?

And that, my friends, more or less wraps up this experiment-in-thought in fragments. This is an experiment whose outcome matters less than all that transpired in the middle, because education and life—as I’ve come to understand my own—is much more about the experience (as disorienting and unsettling as it can be) than about where you end up. As with many of my own lab experiments back at Wellesley, I will likely need to revisit the process, return to what started it all, and perhaps search anew. But I guess that is research. And this was an experiment.